Professional graphite material supplier, graphite for EV, grease, furnace and any other industries.

Overview of the solid electrolyte interface of the graphite anode

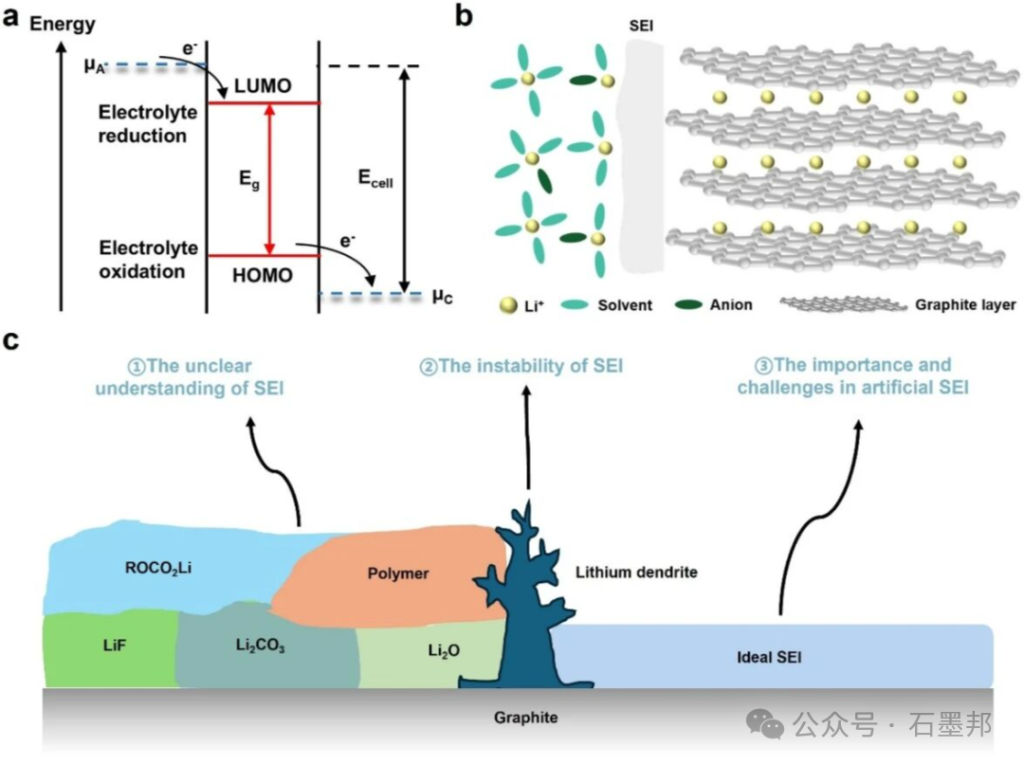

SEI formation is closely related to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) and highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) energy levels of the electrolyte. During the initial charging process, the graphite negative electrode potential is lower than the reduction potential of the electrolyte, causing the solvent and lithium salt to undergo reduction decomposition and generate an SEI layer, typically a few nanometers to hundreds of nanometers thick, uniformly covering the graphite surface.

As a critical interface layer controlling battery performance, the inherent randomness and dynamic instability of the SEI (Sediment Layer) hinder the optimization of its composition and structure to meet the demands of extreme operating conditions, especially in fast charging and low-temperature scenarios. These limitations create bottlenecks in lithium-ion transport and increase the risk of mechanical failure. Therefore, the rational design of artificial SEIs (considering the synergistic effects of composition, structure, and function) and the development of advanced characterization techniques to explore the dynamic changes of the SEI are crucial for overcoming these bottlenecks and realizing next-generation high-stability lithium-ion batteries.

Artificial Construction and Engineering Strategies for Solid Electrolyte Interfaces

In an ideal SEI, the inorganic component should exhibit excellent Li+ transport properties, electronic insulation, mechanical strength, and high thermal stability, while the organic component can typically provide flexibility to accommodate the stress caused by volume changes in the electrode during charge-discharge cycles.

2.1. Construction and Regulation of Inorganic-Rich Solid Electrolyte Interface Layers

LiF is a common yet complex component in the solid electrolyte interface layer of lithium-ion batteries. On the one hand, theoretical studies show that it possesses a high Li+ diffusion barrier (0.729 eV) and extremely low ionic conductivity (10−13–10−14 S cm−1), which hinders ion transport and limits battery performance under fast-charging conditions. On the other hand, LiF exhibits a high electron tunneling barrier, a large shear modulus, and excellent chemical and electrochemical stability, making it a key factor in interface robustness. Specifically, LiF can suppress the decomposition of LiPF6 and inhibit dendrite formation, thereby improving the cycle stability of lithium-ion and lithium metal batteries.

Li₂O has a relatively high ionic conductivity (approximately 10⁻⁹ S cm⁻¹) and a low Li⁺ transport activation energy (0.58 eV), and therefore has attracted increasing research attention in recent years.Li₂O crystals in the SEI layer can act as nucleophilic centers, promoting the decomposition of ester solvents in the electrolyte and thus contributing to the formation of a characteristic mosaic-like SEI structure. It has been reported that Li₂O can reversibly adsorb within the SEI layer, providing additional capacity; this phenomenon can be verified by measurements using a quartz crystal microbalance. Recent studies have shown that among various SEI components, the coulombic efficiency of lithium metal batteries correlates most strongly with Li₂O. Therefore, Li₂O is increasingly considered one of the most promising and beneficial SEI components.

Li₂CO₃ is also a common natural component in SEI (Sediment-Insulated Zone), and it can further decompose into Li₂O. Similar to Li₂O, Li₂CO₃ also contributes to the formation of efficient lithium-ion transport channels within the SEI. On the one hand, due to its abundant lithium vacancies, Li₂CO₃ exhibits a relatively low Li⁺ diffusion barrier (0.227 – 0.491 eV), far lower than LiF, thus helping to improve the lithium-ion diffusion coefficient in the SEI.On the other hand, Li₂CO₃ exhibits synergistic effects with other inorganic SEI components. For example, the space charge accumulated at the LiF/Li₂CO₃ heterojunction can further accelerate lithium-ion transport within the SEI. Furthermore, Li₂CO₃ possesses high chemical stability and tends to form a continuous and uniform morphology, which not only suppresses electrolyte side reactions on the negative electrode surface but also enhances the robustness of the SEI during repeated damage-repair cycles in long-term operation.

In recent years, as demand for fast-charging batteries has increased, phosphorus-based anodes have attracted significant attention for their high theoretical capacity, suitable reaction voltage, and abundant reserves. Although challenges remain regarding their reaction kinetics and structural stability, phosphorus-containing compounds have been used as beneficial components to improve the solid electrolyte interface, thereby enhancing the rate and low-temperature performance of graphite-based lithium-ion batteries.

Numerous studies have shown that the effective ionic conductivity of SEI films is typically higher than the individual conductivity of its components, indicating that Li+ migration in SEIs involves synergistic effects among multiple components. For example, Li₂CO₃ possesses relatively high ionic conductivity, while LiF is an electronic insulator. Individually, neither can achieve ideal SEI functionality; however, when they coexist, they form a heterostructure that enhances ion transport and improves the electronic insulation properties of the anode interface. Similar synergistic effects have been observed between LiF and Li₂O. Furthermore, the abundant grain boundaries within the SEI further promote Li+ diffusion, contributing to uniform and stable deposition and stripping cycling at high current densities.

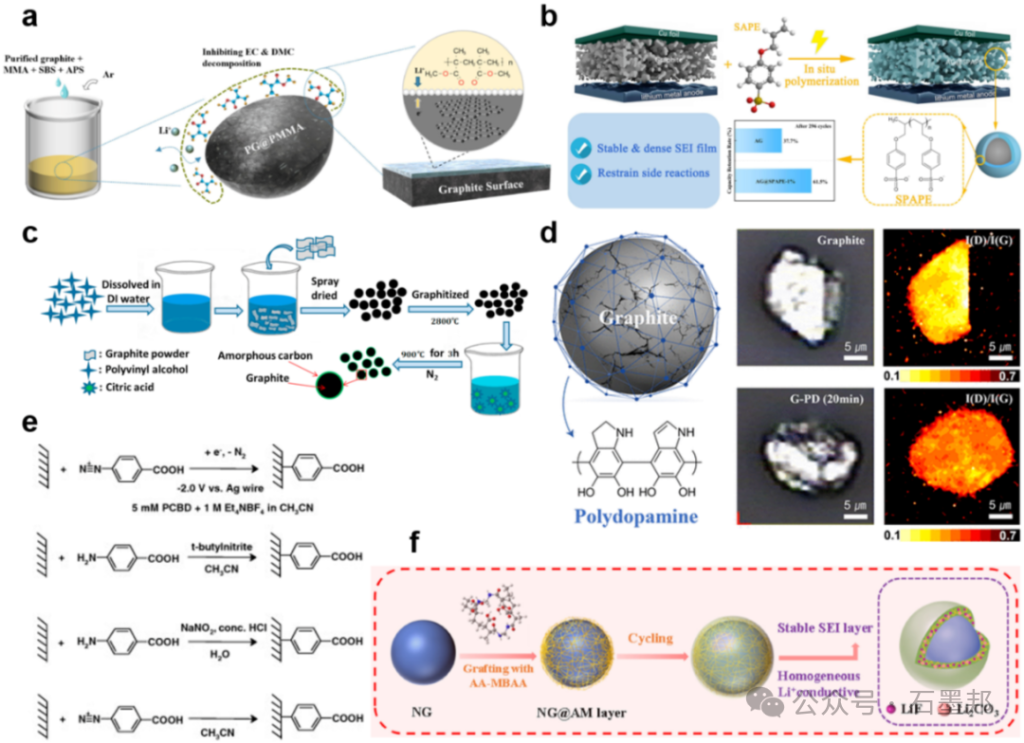

2.2. Construction and Regulation of Organic SEI Components

The SEI region adjacent to the electrolyte is primarily composed of organic products from the reduction and decomposition of the electrolyte solvent, with a small amount originating from residual solvent. Since the commercialization of lithium-ion batteries, carbonate-based electrolytes have been widely used. Typically, carbonate-based electrolytes use a mixture of cyclic and linear carbonates as solvents. Linear carbonates, such as dimethyl carbonate (DMC) and ethyl methyl carbonate (EMC), generally decompose into short-chain fragments. In contrast, cyclic carbonates, including ethylene carbonate (EC) and propylene carbonate (PC), undergo ring-opening reactions to form long-chain hemicarbonates, which contribute to enhancing the robustness and flexibility of the SEI.。The design principles of organic SEI components can be summarized into two key objectives: (i) improving mechanical flexibility; and (ii) optimizing the spatial distribution of organic matter within the electric double layer. Modification strategies for graphite-based SEIs are typically classified according to the functional groups of the organic components, such as ester, ether, hydroxyl, amino, and carboxyl groups.

2.3. Artificial Intelligence-Assisted SEI Design and Performance Prediction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is emerging as a transformative tool for elucidating the complex mechanisms of SEI formation and evolution on graphite anodes. SEI is a dynamic, multi-component, and metastable interfacial layer, whose structural and chemical heterogeneity renders traditional trial-and-error optimization methods inefficient. Combining AI-driven analysis with first-principles calculations and experimental data enables a more comprehensive and predictive understanding of interfacial phenomena.

Artificial intelligence has established a new paradigm for SEI research: shifting from empirical optimization to data-driven mechanism understanding and predictive design. Its integration with in-situ characterization, high-throughput computing, and materials informatics is expected to systematically guide the development of next-generation artificial bilayer and robust graphite anode solid-state electrolyte interfaces, achieving a balance between chemical reactivity, ion transport, and mechanical stability.

Evaluation and characterization methods for solid electrolyte interfaces

3.1. Morphological and structural characterization of SEI

The surface morphology of SEI is not merely a surface feature, but a direct reflection and determinant of its physicochemical properties. Advanced imaging techniques provide key tools for visualizing lithium deposition kinetics and SEI growth kinetics.

3.2. Characterization of SEI chemical composition

The chemical composition of the electrolyte interphase (SEI) fundamentally controls interfacial ion transport, mechanical integrity, and degradation kinetics in rechargeable batteries. Since the SEI is a complex mixture of organic and inorganic phases formed through electrolyte decomposition, accurately understanding its composition is crucial for elucidating capacity decay mechanisms and rationally designing stable, high-performance electrodes.

3.3. Characterization of the electrical properties of SEI

An ideal SEI should possess both high ionic conductivity and strong electronic insulation; therefore, evaluating its electrical properties and the corresponding battery electrochemical performance is crucial.

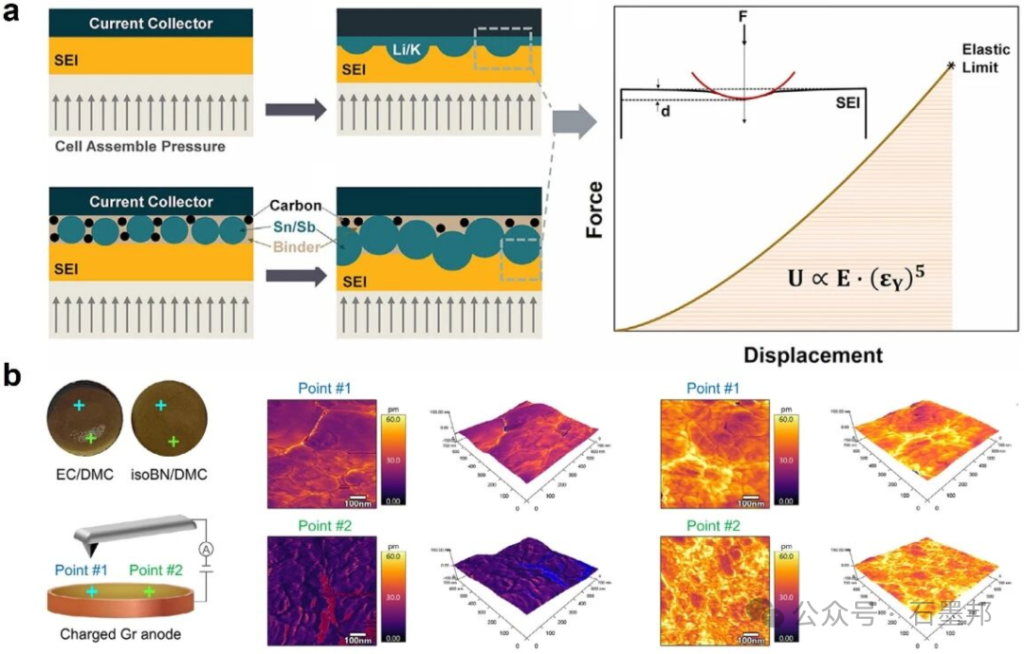

3.4. Characterization of the mechanical properties of SEI

Repeated Li+ insertion and extraction cause volume expansion and contraction of the graphite anode, generating mechanical stress within the SEI (Sediment Injection Layer). When the stress exceeds the SEI’s strain tolerance, the SEI fractures, exposing fresh electrode surface to the electrolyte and triggering side reactions that regenerate the SEI, ultimately accelerating battery capacity decay. Therefore, the mechanical stability of the SEI is crucial to battery performance, requiring rigorous characterization of its mechanical properties.

3.5. Characterization of the thermal properties of SEI

Some SEI components are unstable and easily decompose at temperatures as low as 60 °C, generating significant heat and flammable gases, which can trigger a chain reaction during thermal runaway. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that the thermal transport properties of typical inorganic components vary. The thermal conductivity order of the crystalline phases is as follows: Li₂O (approximately 20 W/(m·K)) > LiF (10 W/(m·K)) > Li₂CO₃ (4.75 W/(m·K)). Increasing the proportion of high thermal conductivity components can enhance overall thermal conductivity, while a higher Li₂CO₃ content will decrease thermal conductivity. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the thermal properties of SEIs and their decomposition processes is necessary before improving the intrinsic safety of lithium-ion batteries.

Conclusion and Outlook

Despite significant progress in SEI design over the past two decades, existing strategies still struggle to support the stable operation of lithium-ion batteries under extreme conditions. While electrolyte or additive regulation is effective, it is constrained by practical limitations such as bipolar compatibility, system complexity, and potential side reactions. High-concentration salt systems, while optimizing SEI, introduce process challenges such as increased viscosity, hindered wetting, and increased costs. Meanwhile, the artificially constructed inner SEI and the electrolyte-induced outer SEI often exhibit structural mismatch, leading to localized stress, crack propagation, and rapid degradation. Traditional post-construction characterization methods also struggle to capture the dynamic changes in the SEI. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop SEI architecture design methods with both lateral and vertical gradient control capabilities, and to establish in-situ/operational characterization techniques that can correlate atomic-scale mechanisms with battery performance under operating conditions.

Future SEI research can focus on five directions: First, developing graphite materials with pre-defined functions, improving diffusivity, conductivity, and structural stability by controlling surface chemistry, morphology, and elemental doping; second, systematically exploring beneficial SEI components, achieving targeted design of components and optimization of rapid ion transport mechanisms through theoretical calculations and mechanistic studies; third, establishing scalable SEI modification strategies, clarifying their formation mechanisms, and avoiding remaining at the laboratory proof-of-concept stage.; Fourth, develop real-time, non-destructive, and high-precision dynamic characterization methods to reveal the evolutionary behavior of SEI under actual battery conditions. Fifth, strengthen the application of AI in SEI research, using high-throughput experiments, data-driven modeling, and multi-dimensional analysis to facilitate efficient SEI design and performance prediction. Combining these directions will provide a systematic path for building truly functional and applicable SEIs.