Professional graphite material supplier, graphite for EV, grease, furnace and any other industries.

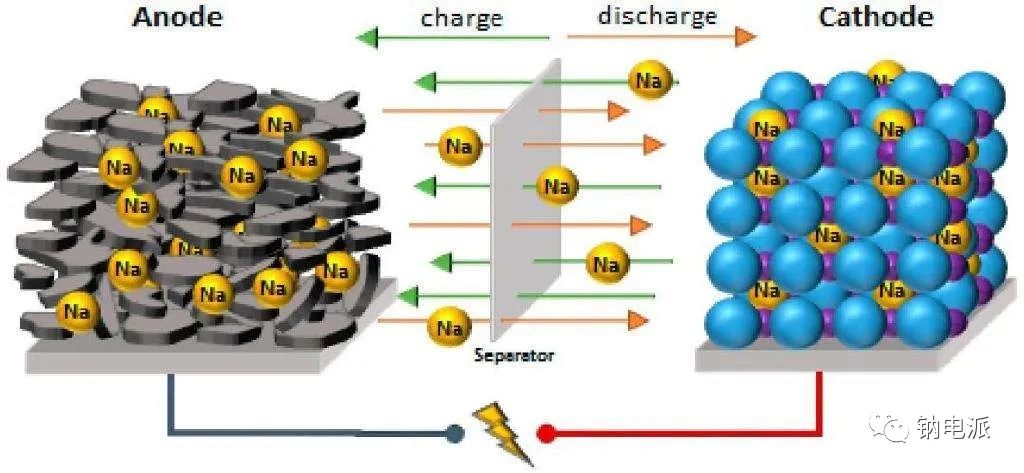

Sodium-ion batteries, a rising star in the energy storage field, are undergoing accelerated industrialization worldwide. Similar to mature lithium-ion battery systems, the anode material is a crucial factor determining the performance, cost, and safety of sodium batteries. However, the fundamental differences in the physicochemical properties of sodium ions and lithium ions mean that sodium-ion anodes are not simply a replication of lithium-ion battery materials; they open up a unique and challenging innovation track.

Sodium ions have a relatively large radius, making it difficult for them to be efficiently and reversibly embedded in the traditional graphite layered structure like lithium ions. Therefore, the mainstream graphite anode in lithium-ion batteries exhibits extremely low capacity in sodium-based battery systems, directly spurring the exploration of entirely new material systems. Currently, research and development of sodium-based anodes primarily focus on carbon-based materials, titanium-based compounds, and alloy materials, with each path seeking to achieve an optimal balance among capacity, rate capability, lifetime, cost, and safety.

Hard carbon is currently the closest sodium electrode material to commercial application and is highly anticipated by the industry. It is a carbon material that is difficult to graphitize at high temperatures. Its interior is not arranged in a regular layered structure like graphite, but is composed of disordered graphite microcrystals, nanopores, and defects. This unique “randomized layer structure” provides multiple storage sites for sodium ions: ions can be adsorbed on the surface, fill micropores, or embedded between graphite microcrystals. Therefore, hard carbon typically offers high reversible capacity and excellent cycling stability, and its raw materials are widely available (such as biomass and resins), making costs manageable. However, its low first-cycle efficiency and voltage plateau lag remain key areas for current R&D optimization.

In contrast to hard carbon, soft carbon can be partially graphitized at higher temperatures. Soft carbon typically exhibits better electronic conductivity and a lower sodium storage potential, which is beneficial for improving battery power output and energy efficiency. However, its reversible capacity is generally lower than that of hard carbon. Improving the overall performance of soft carbon is mainly achieved through precursor selection, process control, and compounding with other materials.

Besides carbon materials, titanium-based oxides (such as sodium titanate) are another important anode choice. These materials are based on intercalation/extraction reactions, exhibiting minimal volume change, ultra-long cycle life, and excellent safety, along with a high charge/discharge platform that avoids the risk of sodium deposition. However, their theoretical capacity is relatively low, and their electronic conductivity is generally limited, restricting their application in high-energy-density scenarios. They are more suitable for specific energy storage applications with stringent requirements for lifespan and power.

To meet future demands for higher energy density, alloy-based (such as tin, antimony, and phosphorus) and conversion-based anode materials have shown great potential. They can react with multiple sodium ions, providing a mass capacity far exceeding that of carbon materials and titanium-based oxides. However, the dramatic volume expansion (potentially exceeding 300%) during the reaction can lead to material pulverization, electrode structure collapse, and rapid deterioration of cycle performance. This is a global scientific challenge in this field. Current strategies primarily aim to buffer stress through nanostructuring, compositing with elastic carbon matrices, and designing special microstructures, but large-scale practical application remains a long way off.

In summary, the development of sodium-ion battery anode materials exhibits a diversified pattern, unlike lithium-ion batteries, where a single dominant material has yet to emerge. Currently, pioneers in industrialization generally choose hard carbon as their first choice due to its optimal balance between overall performance and cost. Titanium-based materials occupy a niche market due to their safety profile, while alloy materials represent a future breakthrough direction.

The competition in this field is essentially a race of microstructure design, interface control, and low-cost engineering capabilities. From the ingenious conversion of biomass waste to prepare hard carbon with uniform performance, to building buffer structures at the atomic scale to manage the dramatic volume changes of alloys, every step forward embodies the wisdom of materials science. The evolution of sodium-ion batteries is not only crucial for their successful establishment in the energy storage and lightweight electric vehicle markets, but it may also pave the way for new material paradigms for future battery systems with lower costs and more abundant resources. Its maturity will become a vital technological cornerstone in the energy transition.